Well even animals do it, they groom each other. For hours, tidying their fur. Male species engage in theatrical dances to show off their grooming and impress females in mating season. Cats lick themselves all day long. And humans… well, we have plastic surgery, nail bars and hairdressers. So why is it that the practice of beautifying yourself carries so many debatable questions?

The answer might rely on the term scientists have chosen for the field: “plastics intervention surgery.” But should we really view all the parts of the beauty & co industry with thesame doubtful eyes? The pursuit to be beautiful can also take the form of exercising, dieting, buyinga pretty dress – so why should we judge plastic surgery as worse?

It is when it evolves into a conformity phenomenon, and societal pressure – when a non-conform face seems unusual in a crowd – that we see the rabid results, a regime of taste begins and questions the innate variety of human appearances. To illustrate: open up the pages of a Lebanese society magazine, (yes any of the hundreds), and ponder about the expressions of the characters featured. “They all look the same – are you on

“halwassah” drugs? No, more likely it’s the curious landscape: zenga zenga, on everystreet.”

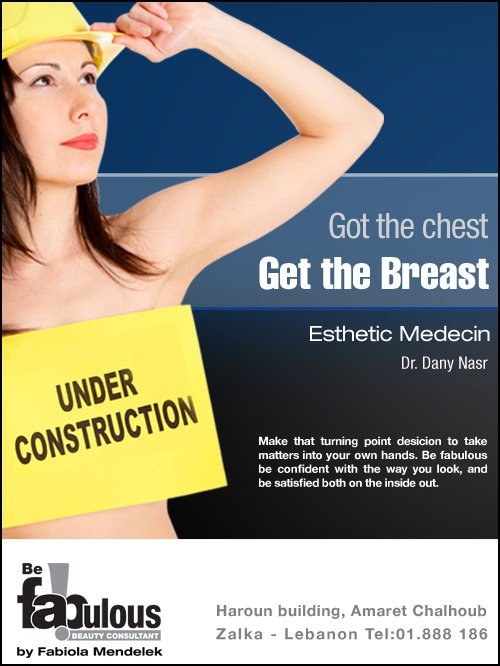

Someone could easily be heard here saying, “Make me more like Haifa the singer, and less like my aunt and sister!” or “Hello, my name is Sophia, and I am currently under construction… umm… plastically speaking.” Forget all the little expressions and quirks that typify someone into a uniquely identifiable person.

Why do women follow these models? Is it only a question of fashion? After all, other cities around the world seem to be engulfed in the same practices of beauty. But for a small country like Lebanon, the percentage of people undergoing plastic surgery is among the highest in the world, and so becomes a case in point.

But a question of identity follows, which should be taken in context: That of a not-really-functional country, ridden with poverty, corruption and immigration; A city whose fabric is ravaged by feral real estate, succumbing to a disregard for heritage, and constantly promoted as a place for parties and nightclubs. An image adopted by its own Ministry of Tourism, making graphic innuendos by parading lightly clad Lebanese girls in their promotional message. Is it not telling that the national carrier airline chooses in its welcome message to parade plastic surgery centers – along with before and after pictures?! How is that relevant to a place as topographically varied as the ethnicities inhabiting it? The country itself seems like it is morphing into – well, what though…?

But behind tending and modifying physical appearance lies also a quest for something else: Is changing one’s features an erasure of an old unwanted state of skin, like some coming of age ritual? And what does this ritual hide, actually? What does this different, adopted, mask betray? What additional arms against this brave new world do these new appendages add? Is an un-fabricated looking person somehow more vulnerable?

Are these make-over rituals to be seen through the lens of the newly globalized world, where looking a certain way prevents the easy access permitted by more “generic” features? Where being viewed “foreign” actually further distances you from others in the smaller global village? Have all traces of origins, like local languages, become social barriers and thus must be carefully masked under the label of internationalization? Is beauty not also influenced by the same trend?

But one does not need to dig so deep behind this phenomenon to acknowledge that Lebanese society is one that is actually based on appearances, where a person with limited means feels compelled to still buy that expensive car to save face. A country where its people are socialized into putting vast amounts of emphasis and time on their looks, be they girls or boys or the newly hyped metrosexuals. This mentality goes hand in hand with how the city and its people construct themselves, on caring for the exterior, more frivolous, appearance.

Many authors have compared a city to a woman. And the parallel goes beyond the sailor’s “girl for every port” expression. Here the parallels drawn tell the story of a place unable to deal with its own issues, always on the edge of breaking up into civil strife. Adept only to revel in its pubs clubs and restaurants, serving as a playground to its wanting neighbors. This is its assumed identity, an outward appearance – and perhaps how it survives.

Publisher:

Section:

Category: