It feels inappropriate to write about this. Somehow, not quite right to make yet another plea, to use words for an issue that should not even be discussed anymore. Least of all in discussion about a right that is as “right” as they come, as basic and uncompromising as they can possibly be. An automatic right, like the reflex to breathe when one is given life. Or when one looks for an identity. An issue that shouldn’t warrant one single debate more, with no words added.

For that is the magic of justice, it is inherent, an instinctual sense inseparable from dignity, visceral, by which all of us can understand each other, and the struggle of the common man.

Or, here, woman.

In a discussion with friends recently, someone was surprised to learn that a man who has relinquished his Lebanese citizenship, thrown it away, decided he did not want it anymore, determined that he would rather be without it… this man could get it back if he changed his mind, with a few exceptions.

How does that work in a country where having a Lebanese mother does not grant you any right to claim Lebanese origins, be they only biological, if not also cultural, historical, emotional? Where a foreign woman enjoys more rights than a Lebanese one just by virtue of marriage to a Lebanese man? (Where wedding a Lebanese man gains you and your kin Lebanese citizenship, while a Lebanese woman cannot pass on her nationality to a foreign spouse, nor to her kids.)

And so I ask myself, why bother to write again.

Why are we still asking this same question, and not raising it also in anger, refusing to accept it. What is it exactly that still stands between us and the ability to mobilize in bigger numbers in the face of an injustice so blatant and degrading that it ultimately negates its own and treats as alien half of the human beings breathing under its sky.

None of the arguments advanced in response to the nationality question by those with the power to change the status quo are convincing.

There is the supposed idea that granting citizenship to the children of a Lebanese mother would invariably threaten the delicate balance of ethnicities and religions living in these narrow borders – an argument which is not only racist, but also a backhand excuse, which tries to play on sectarian fears and fear of the other to abort the issue. It serves only to further prove the fear and genuine disregard the state shows to its citizens, all of them.

Of all the attempts at mobilizing and re-working the laws that associations and NGOs put forward, not one of them has come close to getting at least some kind of compromise by those with the executive power to change this law. Granting a 3-year residency permit for children of a Lebanese mother – viewed as illegal at the age of 18 and forced to leave the country then, doesn’t count. It is feigning generosity, like handing a beggar few pieces of change, a postponement for flashing the exit sign.

This sick concoction was born from the loins of a Lebanese legal system inherited from French colonialism, modeled after the French 3rd republic civil code. In essence, it is a Napoleonic code from the 18th century, where married French women were legally accorded the status of a minor1. The past 300 years have failed to leave any imprint of progress, it seems. Instead, the Lebanese nationality laws epitomize archaism combined with sectarianism and patriarchy, creating a potent, toxic combination to entrench gender bias.

Know this: The State you were born in, the country of your mothers and fathers, is a country that engages in continuous and relentless efforts to undermine any change to this prejudiced law. A country where, in 2010, the Ministry of Justice filed an appeal against a landmark court decision allowing a Lebanese mother to pass on her nationality to her children, born of a foreign father who passed away.

This is your state, your justice. Rebel against it.

So I ask myself, why bother writing about it? Why bother, when all the voices in this small broken country that is incapable of caring for itself should have already come together to ask a million questions about this – and should have found an answer long ago.

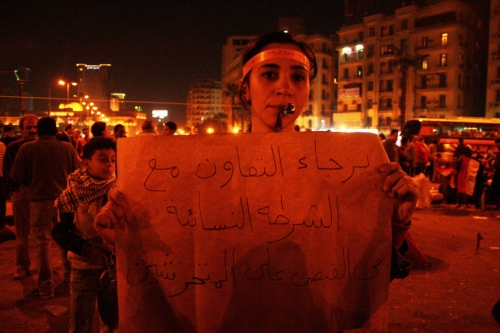

In this time of revolts, when repressed freedoms and rights the system has disavowed are all coming ashore, shouldn’t a fundamental injustice be rectified? Isn’t it now or never? Shouldn’t the right to the nationality have a revolt, a demonstration of its own, with the streets taken and the squares filled with rebellious clamor against this openly derogatory gender discrimination?

It’s the answer we did not find. It’s all about timing, about coordination, a harmony in composition, like in a melody. The answer is not yet found, because the demand has not been voiced by a unified chorus. And if the notes are dispersed and the tune off beat, then all the voices will be lost and, just like a sinking ship,

we will all drown together.

- McKee, Megan. Lebanon: Women, citizenship and nationality rights. March, 2010. University of Pittsburgh School of Law. http://jurist.law.pitt.edu/dateline/2010/03/lebanon-womens-citizenship-a...

Publisher:

Section:

Category: