In Tori Amos’ autobiographical song about surviving rape (“Me and a Gun” from her first album, Little Earthquakes, 1992), Tori talks abouther choice to wear a “slinky red thing,” and how women's susceptibility to rape is commonly perceived to have something to do with the way they dress or the places they frequent. Funny how, in the tragic story of the rape and murder of Miriam Ashkar in November, no one asked what she was wearing. Was it because, in this case, the perpetrator– a Syrian worker, all too neatly fit the sectarian demonization bill and so no further inquiry was necessary? Or, was it because she was on her way to pray in church in the early evening, her status as a “good girl” thus confirmed? What would the media have said if she were walking alone late at night, or from her boyfriend’s house? Some might have tried to shift the blame from her killer to Miriam herself, as if a woman could ever prepare for rape, or prevent it, or cause it to happen. What if Miriam were divorced or even, married? Then, the crime would pass from her own body to the honor of her husband. This is the Lebanon we live in today. It is a land where only virgins can be raped.

There is an old German saying that a woman’s place is “kinder, kuche, kirche.” (Children, kitchen, church.) It is not hard to see that this mentality is still alive and well in Lebanon. So, how is it that a woman is not safe from harm in any of these three places? (Neither when a child, at home, or on her way to church?) I am currently working on a paper on women’s role in religion in the pre-modern world. When you study history and scripture, you see that patriarchal attitudes towards women are never part of “history” or “tradition,” rather they are political tools that are deployed against women depending on political goals at the time. An example of this would be how American woman were asked to join the workforce during the 1940′s during the patriotic days of WWII only to be sent back to their homes in the 1950′s to breed the next generation of citizens to replace those killed in the war. This is similar to the status of Algerian women after the revolution who were asked to return to their kitchens after playing a vital role in the resistance rather than take up posts in a new post-colonial government. This is not all bad. If patriarchal attitudes are historical products of a time and place, this means that they can also be undone by direct political action. What if, in the spirit of Lysistrata, all wives of Lebanese politicians refused to have sex with their husbands until the new laws were passed? Nadine Labaki’s new film tries to make this point, although I doubt that Russian prostitutes are the answer.

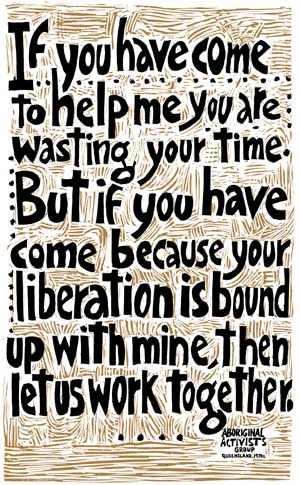

It is to women, all of them, who suffer sexual harassment, abuse, domestic violence, rape and murder that our actions on January 14th should be dedicated, so that we don’t forget the terrible urgency of what we are doing. Lebanon currently has some of the most archaic rape laws in the world. We need new laws to create a safer world for all women residing in Lebanon, whether they are citizens, foreign domestic workers or visitors. And after the laws, we need the courage to enforce them and watch society change.

Tori Amos Song: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uKzCxi2yf5s

Lysistrata story:

http://drama.eserver.org/plays/classical/aristophanes/lysistrata.txt

Publisher:

Section: